Test Types and the Testing Pyramid

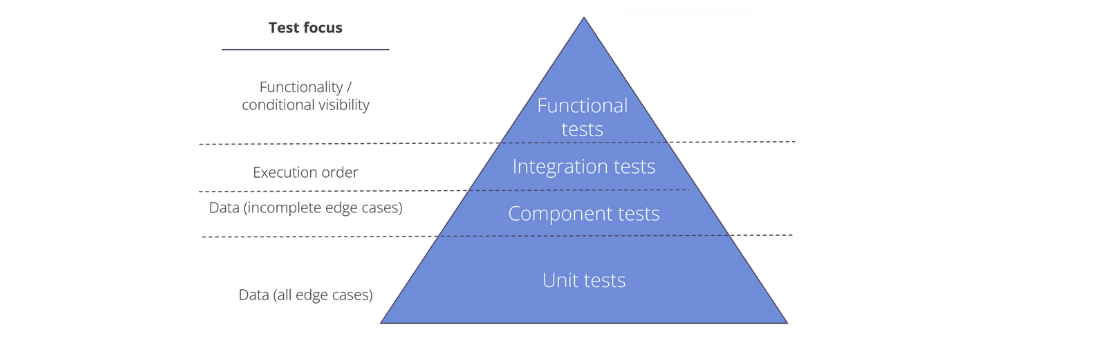

This page details the specific test types required for assessing Mendix applications, ranging from isolated units to end-to-end functionality. It uses the Software Testing Pyramid to structure an efficient and scalable test automation strategy, prioritizing faster, lower-level tests.

1. Test Types

A test type specifies a distinct method for evaluating a Mendix application, detailing its primary objective, the granularity of the logic tested, and the level of coverage achieved. The Menditect Testability Framework adapts traditional test categories to ensure they are applicable for automated testing within the specific Mendix environment. Rather than creating entirely new test typologies, we have aimed to enhance and clarify existing types for the specific context of testing Mendix applications.

Within the Menditect Testability Framework, we define the following test types:

- Unit Tests: The goal of this test is to confirm that a single, isolated microflow delivers predictable data results for all its edge cases, whether it is creating, modifying, retrieving, or validating data. This test is strictly limited to a single microflow that does not call other microflows, referred to as a unit microflow. Read more about this test type in the sub-page Unit Testing.

- Component Tests: This test type assesses the expected data result of an isolated component, which is a collection of microflows that collectively define a specific functionality. Since a component often has too many edge cases for exhaustive testing, this approach focuses primarily on testing only the most critical business scenarios. It verifies the business logic encapsulated within a functional unit, such as an orchestration microflow that calls several sub-microflows. Read more about this test type in the sub-page Component Testing.

- Integration Tests (a.k.a. orchestration test): Unlike Unit or Component Tests, Integration Tests focus on orchestration, validating the correct execution order of units or components based on specific input data. This test confirms that the composition of microflows works as intended, emphasizing the flow and decisions rather than the detailed data output of each individual unit. Read more about this test type in the sub-page Integration Testing.

- Functional Tests: Functional tests operate at the highest level, focusing on the business requirements of the application. They use the application's public interfaces (such as pages or APIs) to verify the end-to-end data results of user actions. Functional tests are designed to confirm that the application meets user expectations and requirements from a black-box perspective, rather than attempting to cover all technical edge cases. Read more about this test type in the sub-page Functional Testing.

2. The Software Testing Pyramid

The Software Testing Pyramid, popularized by Mike Cohn, is a metaphor that organizes different types of software tests into a pyramid shape to show the ideal proportion and focus of each test level. Its core principle is that higher-level tests should build on the results of lower-level tests, creating an efficient and scalable test automation strategy.

The pyramid consists of three levels:

-

Base: Consists of fast and reliable Unit Tests, which verify the smallest building blocks of the application.

-

Middle: This layer contains the Component tests and Integration tests. This approach is a slight deviation from Mike Cohn’s original pyramid, where the middle layer generally combines integration and service tests and typically verifies both execution correctness and data flow together.

-

Top: The top layer features Functional (UI) Tests, which confirm that the application meets user expectations. These tests are the slowest, most fragile and costly to maintain.

Using the Testing Pyramid enables efficient layering and automation of tests for a given coverage level. This approach simplifies tests and makes bug detection faster and less expensive.

The Test Pyramid is often seen as indicating how many tests should exist at each level, with fewer tests at higher layers. Menditect interprets the pyramid primarily as levels of trust: higher-level tests depend on the correctness of lower-level tests. With the Menditect Testability Framework, units could be so small and low-risk, that testing each one individually may not be necessary. Instead, higher-level tests can focus on broader functionality, ensuring efficiency while maintaining confidence in the application.

3. Test Types and the Menditect Testability Framework

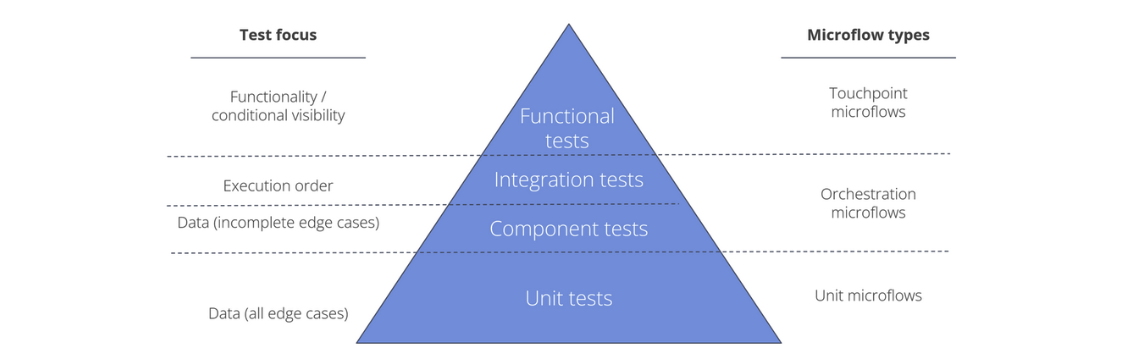

Because Mendix functionality is implemented via microflows, it can be difficult to distinguish the roles of different pieces of logic. The Menditect Testability Framework addresses this by organizing microflows into distinct microflow typologies:

- Unit microflows: Microflows that result in a measurable output, such as an object or attribute change, a created value, or a validation result. They represent the smallest units of business logic. They are the direct targets of Unit Tests.

- Orchestration microflows: Microflows that route the logic to the execution of units but do not change or create values themselves. They serve as the "composition of units" to achieve a desired result. They are targeted by Component Tests (when focusing on data output) and Integration Tests (when focusing on the execution path)

- Touchpoint microflows: These microflows are called from external interfaces (pages, APIs, scheduled events). They serve as the logical entry points for Functional Tests.

The following image shows how these microflow types are associated with the Test Pyramid.

4. Applying the Menditect Testability Framework

By following the Menditect Testability Framework, development teams can structure application logic to enable effective unit and component testing. This builds trust in the lower-level tests, allowing integration tests to focus on the most important process flows. Functional (UI) tests, which are the slowest and most fragile, can then be kept minimal and targeted, reducing the risk of instability.

If an application is poorly structured, the opposite occurs: functional tests become numerous, slow, and fragile, while core business logic receives limited verification, undermining confidence in the system.