Unit Testing

The Unit Test forms the base of the Testing Pyramid. The purpose of this test type is to check if every possible input for a microflow results in a predictable, measurable output. A unit test is executed on one unit microflow.

For a unit test to give reliable results, the microflow's execution must be independent and isolated from external dependencies. Dependencies include elements like database lookup, network calls, or calls to other microflows. If these dependencies exist, the number of data variations needed to fully test the microflow increases dramatically, making the testing process complicated and inefficient.

1. Creating a unit test

Creating a unit test involves the following steps:

- Review dependencies

- Execute Boundary Value Analysis

- Define asserts

- Define the unit test

2. Review dependencies

This step means checking the unit microflow's internal structure for external dependencies. If a unit microflow retrieves data from the database, it is not truly independent. In this situation, your unit test must treat that dependency as an "implicit" input parameter. This requires the unit test to prepare the environment - for instance, by setting up specific data in the database to ensure the microflow gets the expected data when it runs.

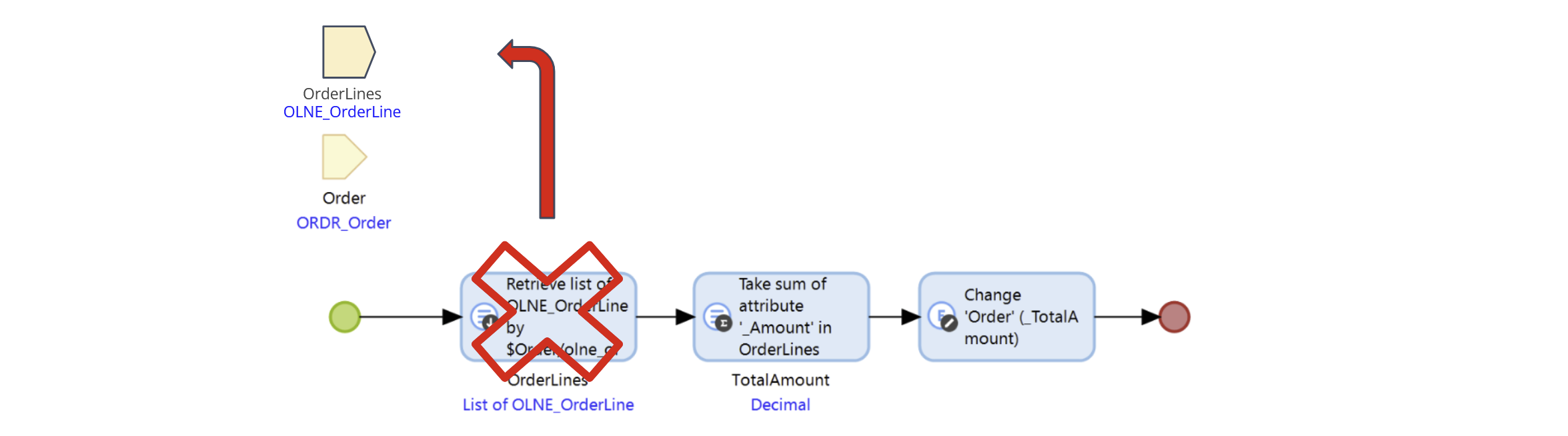

If an implicit dependency is found, the development team should consider converting it into an "explicit" input parameter. This is done by moving the dependent code (like a 'retrieve' action) to the calling microflow and passing the result as a parameter to the unit microflow. This technique is known as Dependency Injection (DI) (see the paragraph about implementing isolatability on the page Key factors of Testability).

3. Execute Boundary Value Analysis

The next step is finding boundary values for the microflow's behavior. A boundary value is an "edge case" for which you expect the software's behavior to change.

If a microflow pre-condition validates that the microflow parameter “driver age” (integer) must be at least 18, the boundary values you must test are:

-

Age is empty

-

Age smaller than 18 (e.g., 17)

-

Age exactly 18

-

Age larger than 18 (e.g., 19)

For each boundary value, the validation should produce a predictable outcome (e.g., TRUE or FALSE).

Finding edge cases requires looking at all parameters - both explicit (passed in) and implicit (retrieved internally) - that the microflow evaluates before running its final logic. This review process also helps uncover missing preconditions. For example, if a microflow calculates an order line amount but fails to check if the 'price' attribute is empty, it could crash the application (a null pointer exception), which is undesirable behavior

The result of this analysis is a list of values that will be used to create the input data variations for your tests in MTA.

One of the more difficult questions is whether an exception should be thrown if a precondition is violated or that this situation is silently ignored. If the situation is ignored, the test should also involve testing for these situations.

4. Define asserts

The final step is to define the specific result you expect for each edge case you identified. Each expected result is defined as an "assert" in your unit test.

When a precondition is violated, the developer must decide whether to throw an exception or ignore the situation silently.

5. Unit test example

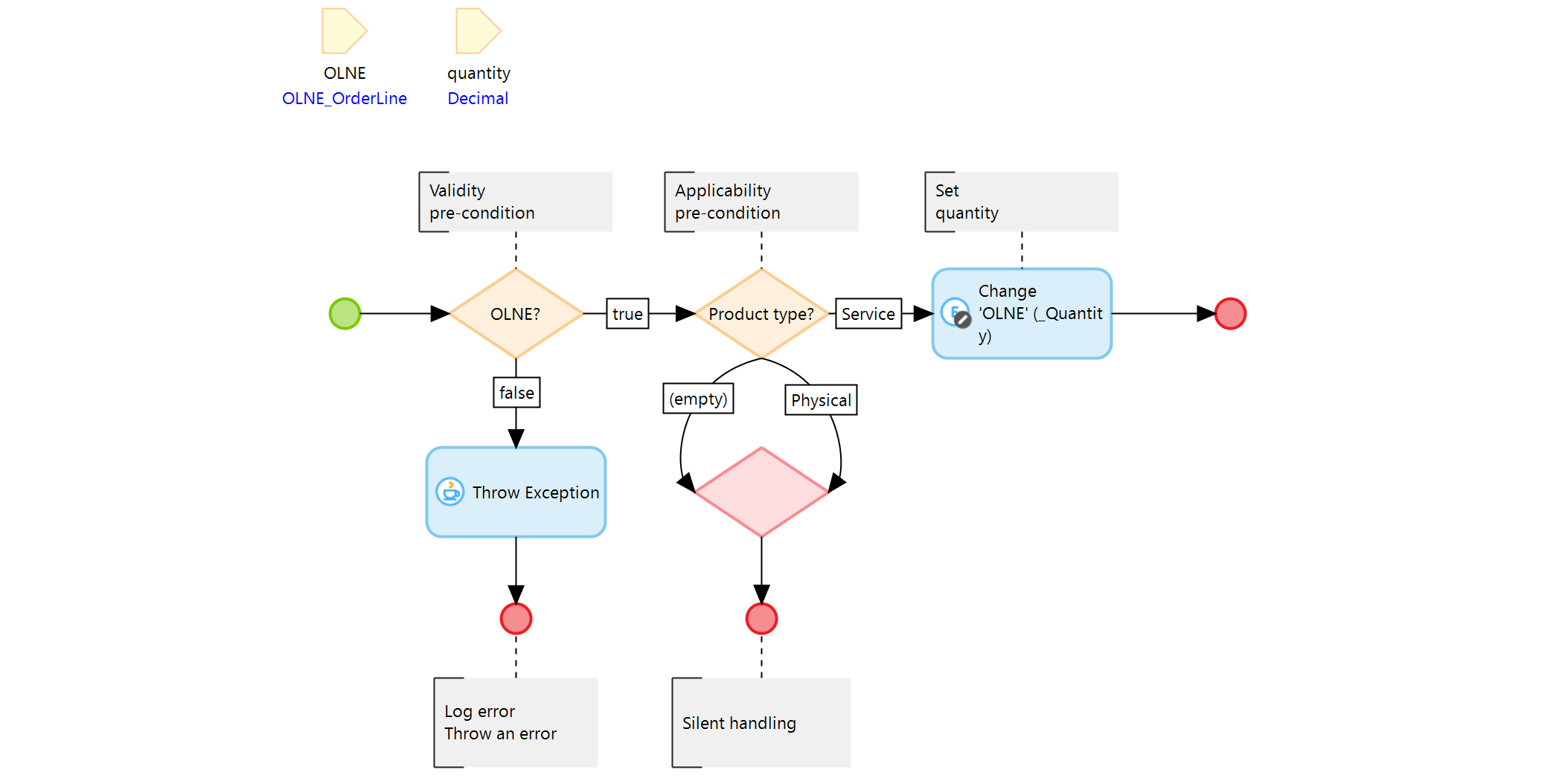

Let's use the unit microflow OPR_orderline_set_quantity as an example for unit testing. The microflow has two input parameters:

- quantity (Decimal)

- OrderLine (

OLNEobject).

There are no preconditions defined for the ‘quantity’ parameter, meaning any value - including empty - is allowed.

However, the OrderLine parameter does have two pre-condtions:

- Whether the OrderLine object is empty, evaluated in the decision ‘OLNE?’.

- The value of the OrderLine attribute ‘producttype’, evaluated in the decision ‘Product type?’

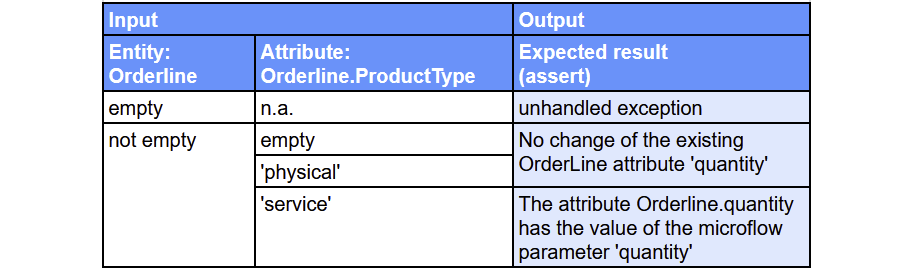

These preconditions and the expected outcomes (asserts) can be combined into a truth table:

The boundary value analysis shows that the microflow currently accepts any quantity value. However, in practice, the business may expect that only positive numbers are valid. This highlights an important point for testers: the expected outcomes (asserts) must be evaluated not only against the implemented logic, but also against the actual business requirements. If the model allows values that the business would reject, this discrepancy should be identified and addressed during testing.