App Components

An application can be vertically divided into components, which encapsulate functionality relatively independent of the rest of the system. While each component is typically implemented as a dedicated Mendix module, large applications might split a module into multiple components using a specialized folder structure.

When creating a component, it is vital to hide its internal logic by making microflows private by default and only publishing those that act as the component's public interface. Components should strive for minimal dependencies on one another, interacting only through these public interfaces to ensure low coupling.

1. Modular Monolith vs. Microservices

Componentization leads to a Modular Monolith architecture, a highly scalable and maintainable structure built on clear segregation of responsibilities.

It is helpful to distinguish this Modular Monolith architecture from a true Microservices architecture, which represents the strongest form of separation. Both structures aim to reduce coupling, but they operate differently:

- In a Modular Monolith, components reside within a single application, sharing the same runtime environment and potentially the same database. Although communication is managed through defined public microflow interfaces, complete isolation is not strictly enforced.

- In a Microservices architecture, each component is an independently deployable application. Communication is strictly enforced through well-defined APIs. This strict separation creates the highest degree of Isolatability and Decomposability. It compels components to follow the rule of "Don't Look for Things. Ask for Things," requiring them to formally request data via API calls rather than accessing data directly.

Although microservices provide better testability because of their strict boundaries, they also bring more operational and architectural complexity. For this reason, the Modular Monolith is a very effective and easier-to-manage option that still offers much better testability than a traditional, unstructured monolith. The Testability Framework focuses on the Modular Monolith, but Menditect’s MTA automated test tool can handle multiple apps in one test setup, which makes cross-application testing possible.

2. Mendix Code Standards

When developing a component, adherence to key code standards is essential:

- Encapsulation: The component's internal workings must be hidden from external components. This is achieved by making microflows private by default, publishing only the public microflows that serve as the official entry points or interfaces.

- Dependencies: Components should aim for low coupling by having minimal dependencies. Any necessary functionality from another component must be accessed only via its public interface. This practice often involves implementing Dependency Injection (DI) patterns to pass required data as parameters, avoiding direct database lookups or hidden cross-component calls.

- Separation of Concerns: Every component should have a single, clearly defined purpose, such as managing all Order functionality, including creation, retrieval, and status updates

3. Layers within Components

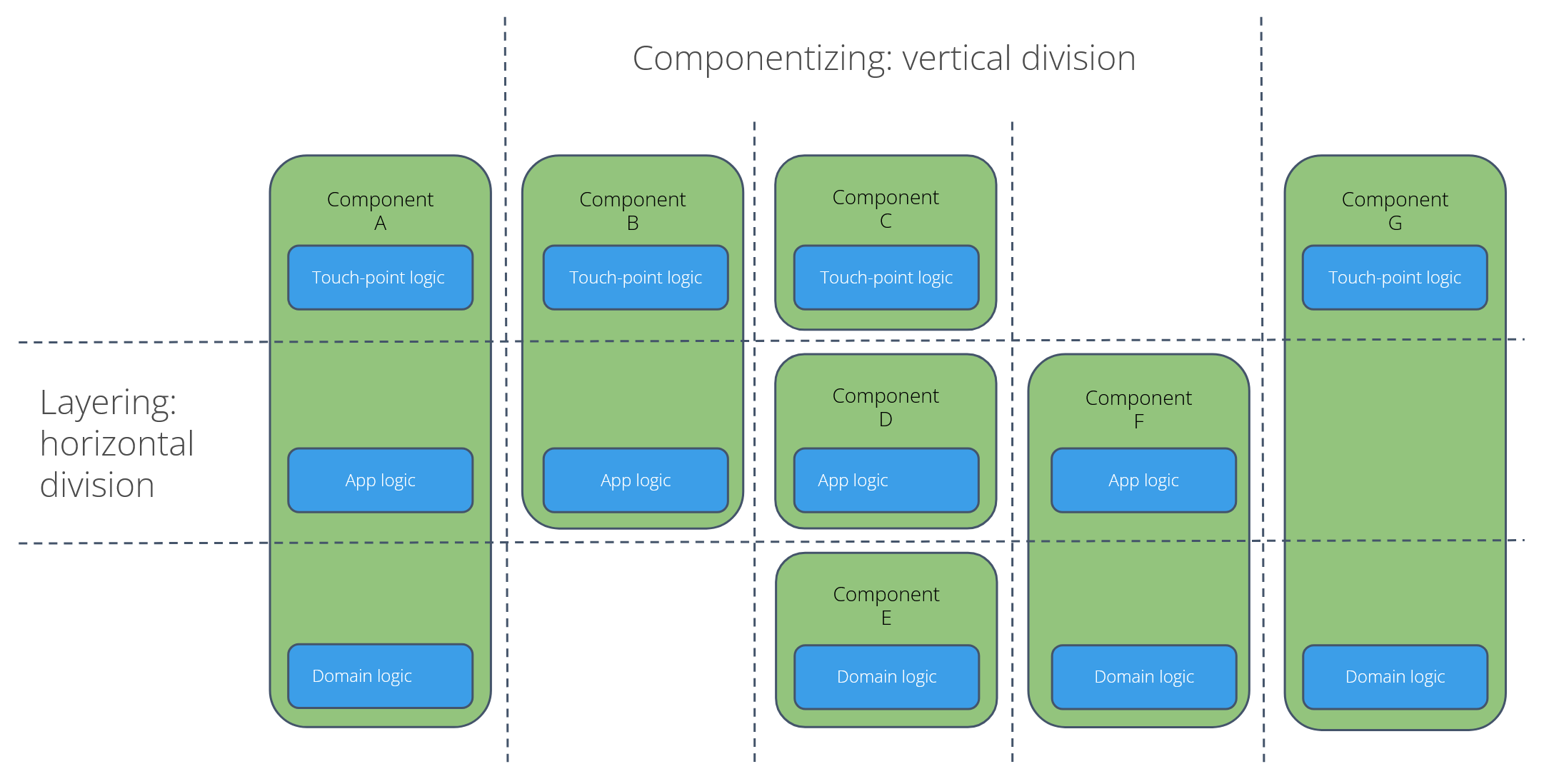

Despite the vertical division into components, each component should still be internally structured using horizontal layers (touchpoint, application, and domain). This structure ensures a testable internal architecture.

The illustration below depicts possible architecture structures through both horizontal (layering) and vertical (component) divisions. This layering follows the Responsibility Flow: User input (Touchpoint) almost always necessitates a business decision (App Logic), which subsequently interacts with data (Domain Logic). This flow explains why it is rare to find Touchpoint logic without App Logic (component C), or App Logic without underlying Domain Logic (Component D).

This component likely would have:

- Touchpoint logic: Pages and microflows for displaying and receiving customer data.

- Application logic: The business processes for creating or updating a customer.

- Domain logic: Microflows that directly interact with the Customer entity, such as validation and data retrieval.

4. Implementing components

Components are implemented as separate Mendix Modules. Smaller components can be organized in dedicated Folders within a module. The horizontal layers are added as sub-folders within the component if the layering is specific to that component.

When a business process spans multiple components, special attention is needed for how the process is structured into steps. Two conceptual modeling approaches are common: depth-first and breadth-first.

4.1. Depth-first processing

A depth-first process handles one task including it’s sub-tasks completely before moving to the next. Like the way cars were made in the early days: each team is building a complete car and only start working on another one when the first one is ready.

In a Mendix microflow hierarchy, microflows call sub-microflows to perform tasks. Depth-first processing executes a sub-microflow and all its nested calls completely before returning to the parent. Each branch is fully processed before moving to the next, following a top-down path. This ensures a predictable order, where the deepest sub-microflows are executed first, and backtracking occurs only after all actions in a branch are complete.

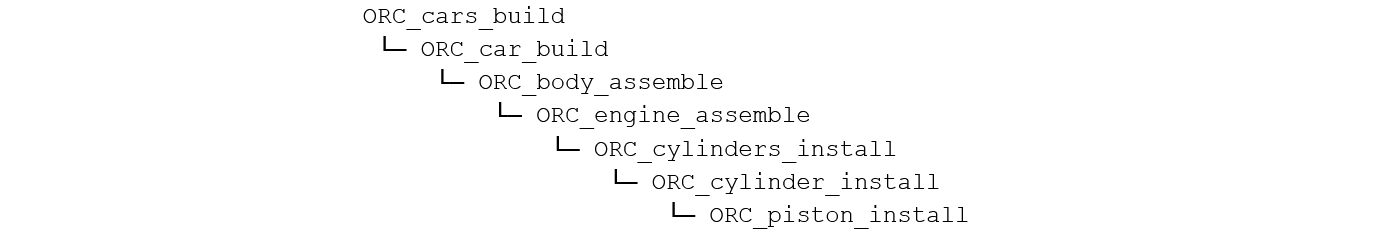

The picture below shows a part of a microflow hierarchy that is creating a one car at the time (depth-first).

The structure of the microflow hierarchy is dictated by the order in which the actions are taken. After all actions are executed, one car finished car is returned to the top orchestration microflow.

4.2. Breadth-first processing

A breadth-first process divides all main-tasks in independent sub-tasks of a certain type. Each sub-task establishes a ‘state’ used to determine if the next sub-task can proceed. When all sub tasks are executed the process is finished.

Synchronous breadth-first processing only moves on to the next sub-task type if all sub-tasks of the previous type are executed. Like the way Ford build cars on an assembly line, where each assembly station is only performing one task. This is typically implemented in one microflow where each sub-task is visible in the main flow.

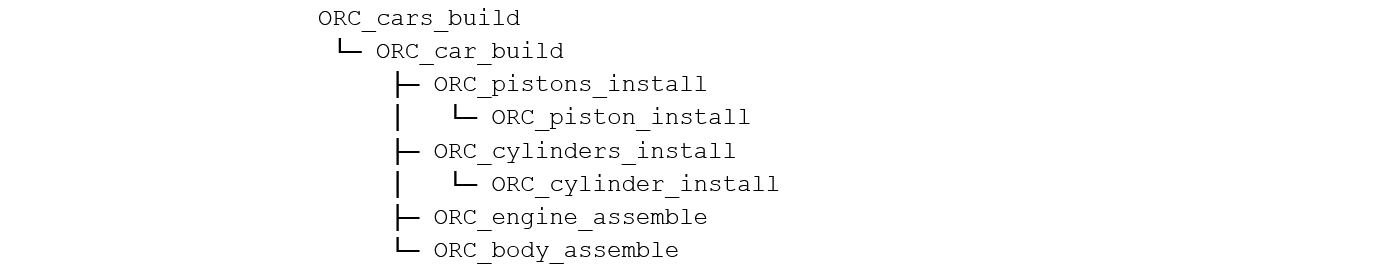

The picture below shows a part of the microflow hierarchy where the creation of a car is executed by executing multiple tasks. Status information is needed if sub-task results are written to the database and retrieved from the database by consecutive steps.

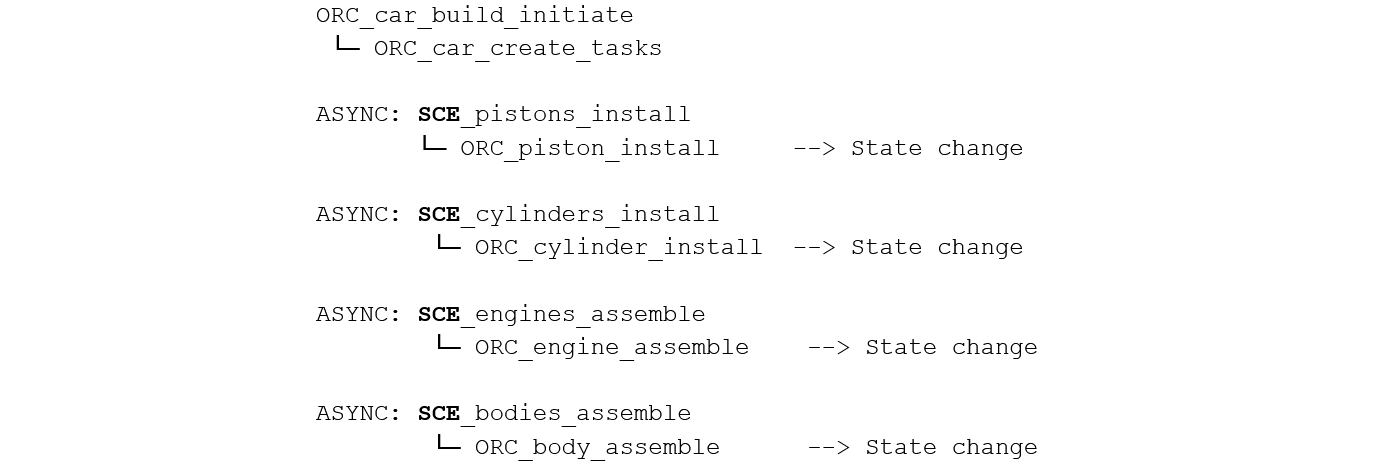

Asynchronous breadth-first processing just creates sub-tasks to be executed, while the actual sub-task execution itself is started as separate asynchronous microflow hierarchies. These asynchronous hierarchies are often initiated by queued tasks or scheduled events.

The ‘manufacture car microflow’ produces the set of tasks that should be handled. Each manufacturing task is executed only if the previous task type is ready. The execution of a task is leading to a state change:

4.3. Evaluating both options

If a process must span multiple components, the breadth-first approach is better. It allows each component to manage one specific task type. This approach enhances maintainability by reducing execution complexity and improves performance by minimizing the objects held in memory and enabling multi-threaded processing. However, implementing breadth-first processing often requires extra state information to the changed objects and pre-conditions to each process step to ensure objects are processed in the correct sequence.